Are positive changes in potential determinants associated with increased fruit and vegetable intakes among primary schoolchildren? Results of two intervention studies in the Netherlands: the Schoolgruiten Project and the Pro Children Study

Ample intake of fruit and vegetables (F&V) is part of dietary recommendations in many countries. However, among schoolchildren across Europe, the reported intake of F&V is lower than recommended1.

According to health behaviour change theories such as the Social Cognitive Theory and2 the Theory of Planned Behaviour3, increasing F&V intake can be induced by changes in presumed behavioural determinants (attitude, social influence, self-efficacy or behavioural control4,5, etc.). Studies on determinants of F&V intake among children have shown that taste preference, availability, parental intake levels, and knowledge of recommended intake levels are of additional potential importance6-9. However, the majority of these studies applied cross-sectional designs, which does not allow concluding upon causal relationships between potential determinants and F&V intake. It may well be that changes in F&V intake precede changes in presumed determinants. For instance, increased exposure to F&V can influence taste preferences10-12. Longitudinal studies are required to better understand the relationships between potential important determinants of F&V intake and F&V intake among children.

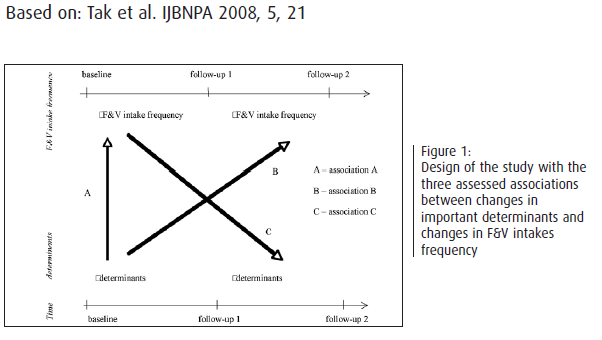

Data from the Dutch part of the Pro Children Study and the Dutch Schoolgruiten Project provide the opportunity to study changes in F&V intake frequency and potential determinants measured at three different time points (Figure 1).

The aim of this study was to investigate whether positive changes in or maintaining high scores on the presumed important determinants of F&V intake in the first time lapse (period between baseline and first follow-up) were associated with positive changes or maintenance of favourable levels in F&V intake frequency in the same time lapse (association A in Figure 1) and with positive changes or maintenance of favourable levels in F&V intake frequency later in time (association B in Figure 1). Further, we examined whether positive changes or maintenance of favourable levels in frequency of F&V intake were associated with positive changes in or maintenance of high scores on the variables that were identified as potentially important determinants of F&V intakes in earlier studies, later in time (association C in Figure 1).

METHODS

This study had a design with a baseline measurement and two follow-up measurements. We only included children from the intervention schools, since these children are more likely to show changes in potential determinants of F&V intake, as a consequence of the intervention activities13,14. The data was used as observational longitudinal cohort data.

Finally, 344 children of the Dutch Schoolgruiten Project (mean age 10.0 years at baseline) and 258 children of the Pro Children Study (mean age of 10.7 years at baseline) completed questionnaires, including questions on general demographics, usual F&V intake frequency, important potential determinants of F&V intake, such as taste preferences of F&V, availability of F&V, knowledge of recommended intake levels of F&V, self-efficacy for eating F&V, and parental influences for eating F&V. The three different associations between changes in determinants of F&V intake and changes in F&V intake frequency were assessed by regression analyses, adjusted for gender, child’s age, educational level of the parents, ethnicity, and region of residence (only for the Schoolgruiten study).

RESULTS

- Relation A – The children who increased or maintained a relatively high frequency of fruit or vegetables intake in the first time lapse were more likely to have increased the following determinants in the same time lapse: liking for both F&V, parental active encouragement to eat F&V, the family rule demanding the child to eat F&V, increased their perceptions of availability at home for fruit, general self-efficacy for eating fruit, modelling behaviour by friends and parents for eating vegetables and parental facilitation of vegetables.

- Relation B – The children who increased or maintained a relatively high frequency of fruit or vegetables intake later in time were more likely to have increased the following determinants in the previous time lapse. Liking of fruit, parental facilitation of vegetables, family rules of eating vegetables (demanding and allowing) and availability at home of vegetables.

- Relation C – Associations were found between increased or stable high frequency of fruit or vegetable intake in the first time lapse and the Following determinants later in time. Increased or maintenance of high scores on liking of both F&V intake and increased or maintenance of high scores of knowledge of recommended intake levels of fruit consumption.

CONCLUSION

This study showed that determinants of F&V intake that appear to be important to induce behaviour change were liking of F&V, facilitation by the parents of F&V, family rules for eating F&V and availability at home of F&V. Furthermore, changes in F&V intake frequency also induced changes in liking of F&V and knowledge of recommended intake levels of fruit. These findings are in accordance with behaviour change theories and support newly proposed theories proposing direct and indirect associations between determinants and behaviour. In addition, the study provides some evidence that behaviour change (increased intake or maintenance of favourable levels of F&V frequency) was preceded by changes in or maintenance of high scores of (some) presumed determinants of F&V intakes, both in the Pro Children Study and in the Schoolgruiten Project. In conclusion, it is important to tailor future interventions aimed at increasing F&V intakes to include these determinants.

References

- Yngve A, Wolf A, Poortvliet E, et al. (2005) Ann Nutr Metab 49, 236-245.

- Bandura A (1997) Self-efficacy. New York: Freeman. In.

- Ajzen I (1991). Organ Behav Hum Decis Process 179-211.

- Baranowski T, Cullen KW & Baranowski J (1999). Annu Rev Nutr 19, 17-40.

- Brug J, Oenema A & Ferreira I (2005). Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 2, 2.

- Bere E & Klepp KI (2004). Public Health Nutr 7, 991-998.

- Rasmussen M, Krolner R, Klepp KI, Lytle L, Brug J, Bere E & Due P (2006). Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 3, 22.

- Blanchette L & Brug J (2005). J Hum Nutr Dietet 18, 431-443.

- Wind M, De Bourdeaudhuij I, te Velde SJ, Sandvik C, Klepp KI, Due P & Brug J (2006). J Nutr Educ Behav 38, 211-221.

- Ball K, Timperio A & Crawford D (2006). Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 3, 33.

- Kremers SP, de Bruijn GJ, Visscher TL, van Mechelen W, de Vries NK & Brug J (2006). Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 3: 9.

- Wardle J, Herrera ML, Cooke L & Gibson EL (2003). Eur J Clin Nutr 57, 341-348.

- te Velde SJ, Brug J, Wind M, Hildonen C, Bjelland M, Perez-Rodrigo C & Klepp KI (2008). Br J Nutr 99, 893-903.

- Tak NI, te Velde SJ & Brug J (2007). Public Health Nutr 10, 1497-1507.