Children’s fruit and vegetable practices and preferences related to parent/child relationships

The family environment has a strong influence on children’s fruit and vegetable (F&V) consumption, but children can also influence the family. Marketing specialists consider children to be influencers; their requests impact parents’ purchases, thus contributing to increasing F&V availability in the home. This increases children’s exposure level, which changes their preferences. However, purchasing and storing F&V does not necessarily make them accessible to children.

An American study1 clarifies the link between demand, availability at home, and children’s F&V consumption based on an intervention completed in 2009-2011 in the US state of Texas. This intervention aimed to stimulate consumption among 9- to 11-year-old children using a game that was tracked for three months (Squire’s Quest II). Parental awareness was increased through newsletters, recipes and advice on a website.

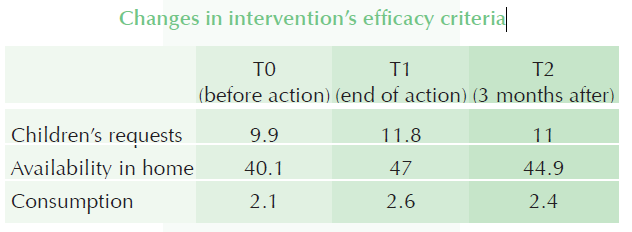

The study was based on a randomised convenience sample of four groups of 100 parent/child pairs. Measurements were taken before the intervention, at the end of the intervention and three months after. They focused on three criteria: (1) frequency child requested F&V over two weeks (1 D = 2 pts); (2) F&V availability at the home measured by the number of F&V over two weeks (1 F&V = 2 pts); (3) child’s food intake measured by number of F&V portions consumed in 24 hours (1 P = 1 pt). The child’s requests and the availability were tracked with a questionnaire. The child’s food intake was measured by summarising what was eaten in 24 hours.

This study shows four main results:

- There is no predictive power between F&V availability and children’s food intake. A previous study showed that a one unit increase in availability led to a 0.14 increase in consumption. This suggests that availability must be significantly increased to have an effect on actual consumption. The intervention focused on children who already consumed some F&V.

- The intervention increased the requests from children and F&V availability in the home, but did not contribute to a significant increase in food intake.

- While the intervention appears to be effective at first glance (criteria increase between T0 and T1), the results are not stable. To guarantee the effect, the intervention’s duration must be sufficient: from nine weeks to four years.

- Parental involvement was low: only 28% read the newsletter and 55% visited the website one to five times during the intervention. Yet it has been demonstrated that direct parental involvement is critical.

F&V availability in the home is necessary but insufficient for stimulating children’s F&V consumption. Parental behaviour towards children is absolutely essential as Vollmer and Baietto have shown2. According to them, a child’s food preferences influence the quality of his or her diet. Yet these preferences are largely influenced by parental attitudes and practices. Therefore, studying causal links between a parent’s dietary practices and a child’s dietary preferences can help guide interventions.

These assertions are based on a study of 148 parents of children aged 3-7 in Illinois using a CFPQ (Comprehensive Feeding Practices Questionnaire) and PALS (Preschool Adapted Food Liking Scale) on fruits, vegetables and foods high in fat and/or sugars. They reveal what the dietary education basics should be to impact children’s behaviours.So, when parents allow children to choose their food, they tend not to prefer fruit. When parents encourage children to participate in making the meal, their preference for vegetables is reinforced. Children prefer high fat and/or sugar foods in cases where parents use food to regulate children’s emotions, use food as a reward, force children to eat more and clean their plate, or severely restrict food considered harmful to health. Restricting foods can be beneficial for children’s diet quality before the age of four, but the situation is the opposite thereafter. In contrast, children pay less attention to fatty and/or sugary foods if parents make healthy food available and accessible in the home, if they prepare healthy food in front of children, and if they explain to children why it is important to eat healthily.

Finally, no significant relationship was found between children’s preference for high-fat, high-sugar foods and the parents’ desire to control children’s weight by encouraging food balance and variety, tracking and restricting.

While it is not possible to determine whether the parent influences the child or vice versa, this study provides evidence that coercive dietary practices are detrimental to a child’s dietary preferences.

In addition, significant fruit and vegetable availability in the home and compassionate, consistent food education improves the child’s interest and consumption. This should guide any interventions with parents intended to improve their children’s food preferences.

References

- DeSmet A., Liu Y., De Bourdeaudhuij I., Baranowski T. and Thompson D. (2017): The effectiveness of asking behaviors among 9–11 year-old children in increasing home availability and children’s intake of fruit and vegetables: results from the Squire’s Quest II self-regulation game intervention. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity (April 2017) 14: 51. DOI 10.1186/s12966-017-0506-y

- Vollmer R. L. and Baietto J. (2017): Practices and preferences: Exploring the relationships between food-related parenting practices and child food preferences for high fat and/or sugar foods, fruits, and vegetables, Appetite 1 June 2017, 113: 134-140.