Cooking at home is associated with better diet quality

Over the past several decades cooking frequency has declined and reliance on prepared foods and foods prepared away from home, both of which are typically more energy dense and of lower nutritional value, has increased1,2. These simultaneous trends are associated with the rise in obesity, which affects more than one-third of adults in the United States3,4.

Time and price constraints, lack of access to healthy foods, lack of knowledge and confidence in cooking skills are all factors that contribute to declines in cooking frequency5. Meals at home are increasingly made with convenience products and prepared or semiprepared items6,7. Cooking at home can provide a high level of control over dietary intake, though certainly not all cooking is healthy cooking, and little is known about the relationship between cooking frequency and diet quality. This study has examined that association.

Americans cook dinner at home an average of 5 nights a week

The study used data from the consumer behavior module of the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES). The NHANES is a nationally representative, cross-sectional population-based survey designed to collect information on the health and behaviors of the US population. The study used data from 2007-2010, and the sample included adults aged 20 and older who were not pregnant or diabetic at time of data collection (N=9,569).

Using 24-hour dietary recall data, diet quality as total calories, protein, fiber, carbohydrates, fat and sugar consumed was measured. An assessment was also made on the consumption of meals eaten not prepared at home, fast food, ready to eat meals and frozen meals. Cooking frequency was measured based on the number of times the respondent or someone in the household cooked dinner in the previous seven days. Cooking frequency was categorized as low (0 to 1 times, N=802), medium (2 to 5 times, N=3,704) and high (6 to 7 times, N=5,063). Measures of body weight, gender, race/ethnicity, education, marital status, country of birth, household size, household food security and income were included in the study. Multivariate linear models were used adjusting for the above covariates to estimate the association between cooking frequency and the dietary measures described above. The study also estimated models using an interaction term between cooking frequency and weight loss intention to examine if the relationship between cooking frequency and diet quality differs depending on whether a person is trying to lose weight. All significance tests were considered at p<0.05.

More frequent cooking at home is associated with better diet quality

Among American adults 20 years or older in 2007-2010, 8% cooked dinner with low frequency, 44% cooked dinner with medium frequency and 48% cooked dinner with high frequency. Blacks were more likely to cook with low or medium frequency than whites. Males and full time workers were more likely to cook with low frequency than females or non-employed individuals respectively.

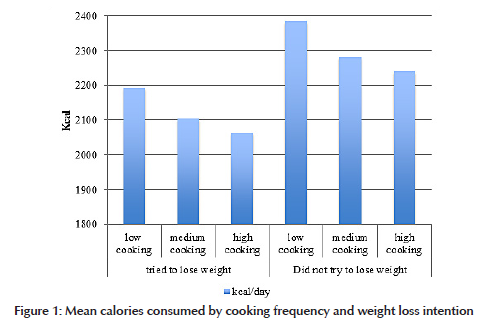

People in high cooking frequency households consumed significantly fewer calories than low frequency cookers (2164 kcal vs. 2301 kcal). High cookers also consumed less carbohydrates (262 grams vs. 284 grams), fat (81 grams vs. 86 grams) and sugar (119 grams vs. 135 grams) compared to low cookers. Higher cooking frequency was associated with better diet quality regardless of whether a person was trying to lose weight. Figure 1 shows calories consumed by cooking frequency and weight loss intention. This pattern was similar for the other measures of diet quality as well.

Helping people cook at home more could have a positive impact on public health

Our findings that more frequent cooking at home is associated with better diet quality regardless of weight loss intention has important implications for obesity prevention and public health. It is important to consider how to best support and incentivize more frequent cooking at home. Cooking skills development through cooking classes, nutrition education and re-introduction of a modern home economic curriculum could all help build cooking self-efficacy, confidence, skills and knowledge. It is also important to address common barriers to cooking: time constraints and lack of access to affordable, high quality, fresh ingredients.

Cooking more frequently may not be achievable for everyone, especially among low-income groups. Therefore, other strategies that make healthy choices and navigating the food environment outside the home easier are urgently needed. Menu labeling, which is set to be implemented nationally in December 2015, has the potential to help people make healthier choices when not preparing their own food.

The Dietary Guidelines for Americans8 encourage Americans to consume smaller portions, less fat and sugar and more fruits and vegetables. New recommendations from the Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee issued in February 2015 go even further by urging a plant-based diet low in sugar, refined grains and red and processed meats9. This study provides evidence that more frequent cooking at home is associated with reduced intake of overall calories, carbohydrates, fat and sugar. Building cooking confidence and skills and reducing barriers to cooking could help more Americans make the healthy choice to cook at home more frequently.

References

- Shao Q, Chin KV. Survey of American food trends and the growing obesity epidemic. Nutrition research and practice. 2011;5(3):253-259.

- McGuire STJE, Mancino L., Lin B-H. . The impact of food away from home on adult diet quality.

ERR-90, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Econ. Res. Serv., February 2010. Advances in nutrition (Bethesda, Md.). 2011;2(5):442-443. - Flegal KM, Carroll MD, Ogden CL, Curtin LR. Prevalence and trends in obesity among US adults, 1999-2008. JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association. 2010;303(3):235-241.

- Cohen DA, Bhatia R. Nutrition standards for away-from-home foods in the USA. Obesity reviews : an official journal of the International Association for the Study of Obesity. 2012;13(7):618-629. Lang T, Caraher M, Dixon P, Carr-Hill R. Cooking skills and health. Health Education Authority; 1999.

- Engler-Stringer R. Food, cooking skills, and health: A literature review. Canadian Journal of Dietetic Practice and Research. 2010;71(3):141-145.

- Chenhall C. Improving cooking and food preparation skills: a synthesis of the evidence to inform program and policy development. Health Canada;2010.

- United States Department of Agriculture and United States Department of Health and Human Services. Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2010. 7th Edition ed. Washington D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office; 2010.

- United States Department of Agriculture. Scientific Report of the 2015 Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee. 2015; http://www.health.gov/dietaryguidelines/2015-scientific-report/PDFs/Scientific-Report-of-the-2015-Dietary-Guidelines-Advisory-Committee.pdf. Accessed March 4, 2015.