WHAT ABOUT VEGETABLES AND FRUIT? »

LINK BETWEEN NUTRITION, DISEASE AND PROSPERITY: Preventing non-communicable diseases by tackling malnutrition

We face a harsh health reality in the developing world. Nutritional deficiencies, predominantly in the form of micronutrient malnutrition, increase the susceptibility to communicable diseases and noncommunicable diseases (NCD) such as heart disease, diabetes and cancer. Many economically developing regions are now suffering a double burden of obesity, diabetes and other related NCDs, on top of nutritional deficiencies and infectious diseases. These all have a significant and negative impact on the lives of individuals that flows over to affect communities, and ultimately harms the economy of nations.

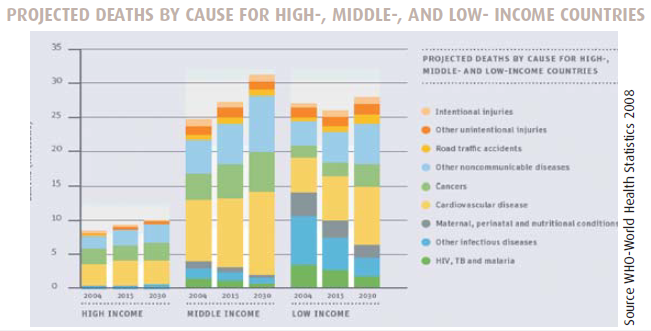

Low and middle income countries are at the centre of both longstanding and new public health challenges. Much is now being spoken about nutritional deficiencies in the context of undernutrition, some two billion people across the world live with hidden hunger; and while important, we also need to focus attention on addressing the NCDs that will cause over three quarters of all deaths in 2030 and will pose additional hardship on already stretched health care budgets.

Hidden hunger

Hidden hunger is defined as micronutrient (vitamin and mineral) deficiency in a person’s diet. It is not malnutrition as classically presented as the hungry or starving individual, but malnutrition as it should properly be defined: poor overall quality of nutrition.

It means that the two billion who suffer from hidden hunger, may eat enough calories to live, but have a basic diet that fails to provide sufficient levels of crucial vitamins and minerals that allows them to be mentally and physically healthy. A key link between undernutrition and NCDs is micronutrients (vitamins and minerals), which yet again mostly affects the world’s poor women and children – further increasing the disparities between the affluent and the poor. The fact remains that women make up little over half of the world’s population, but they account for 60 percent of the world’s hungry. They also produce between 60 and 80 percent of the food in most developing countries where they have less access to land and credit than men do.

The powerful consequences of nutrition transition

Human diet and nutritional status have undergone a number of major shifts over the last three centuries. The concept of the nutrition transition can be defined as a stepwise sequence of characteristic changes in dietary patterns and nutrient intakes associated with societal, economic and cultural changes during the demographic transition of populations. It focuses on shifts in diet, especially its structure and overall composition and is reflected in outcomes such as changes in body stature and body composition, and is paralleled by major changes in health status. A clear example is how changes in European and American diets have caused fluctuations in the average height of men and women throughout time.

Now more than ever, we need to not only understand the dietary and health changes taking place and their consequences, but we also need to define and implement program and policy changes that will positively improve the total nutritional and health status of people in developing economies.

The prevalence of overweight and obesity exceeded that of undernutrition in the majority of 37 developing countries studied as far back as 2005. Recent trends show the rising prevalence has spread and the emergence of obesity has further accelerated not only among adults but also adolescents and even children in the emerging middle class. It is not obesity alone but also diabetes, hypertension, dyslipidemia and arthrosclerosis appear to be on the increase. The reality is that four out of five NCD deaths are in low and middle income countries. This indicates a negative nutrition transition that has serious implications on physical and mental development and performance.

Preventing NCD’s through adequate nutrition

Increasing the consumption of vegetables and fruit, especially traditional but now neglected local vegetables, is also an important but longer term goal to improve the nutritional status in developing countries. Affordability and availability are often the greatest barriers to consumption in consumer research in developing countries but household preferences also pose a significant challenge especially as urbanisation and time pressures increase. For long term success a multiplicity of strategies and interventions at all levels are essential.

References

- For details on the work of SIGHT AND LIFE visit www.sightandlife.org

- For details on the Millennium Development Goals visit www.un.org/millenniumgoals

- For details on the Copenhagen Consensus 2008 visit: www.copenhagenconsensus.com/Home.aspx

- For details on the 1000 Day movement visit: www.thousanddays.org

- For the Scaling Up Nutrition (SUN) documents search on www.unscn.org

- For the Lancet series on Chronic Disease: The Lancet, Volume 376, Issue 9753, 13 November 2010