Patterns of food parenting practices regarding fruit and vegetables among parent-adolescent dyads

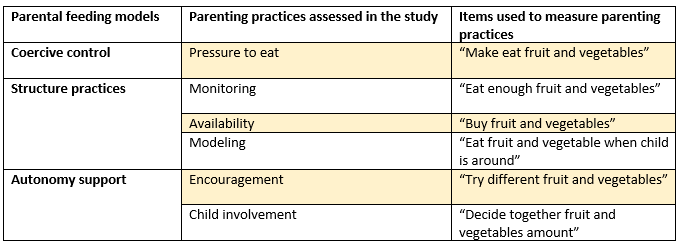

Children’s eating behaviours are influenced by multiple factors. Evidence shows that parental child feeding practices affect children’s food preferences, consumption patterns, and self-regulation of food intake and are associated as well with their weight status (Scaglioni, 2018). Three types of parental feeding practices were proposed as a content map to guide future research (Vaughn, 2016). Structure and autonomy support are generally positively associated with healthful child dietary behaviours while coercive control is associated with negative impacts on children’s eating behaviours.

The present article determines patterns of food parenting practices using a dyadic (concurrent and interdependent), person-oriented approach, according to the three parental feeding models suggested by Vaughn et al. It explores associations between patterns, parent and adolescent characteristics, and dietary intake.

Parents either use multiple fruit and vegetable parenting practices simultaneously or very few to influence their children’s fruit and vegetable intake

Six parenting practices related to fruit and vegetable were measured in this study (Table 1).

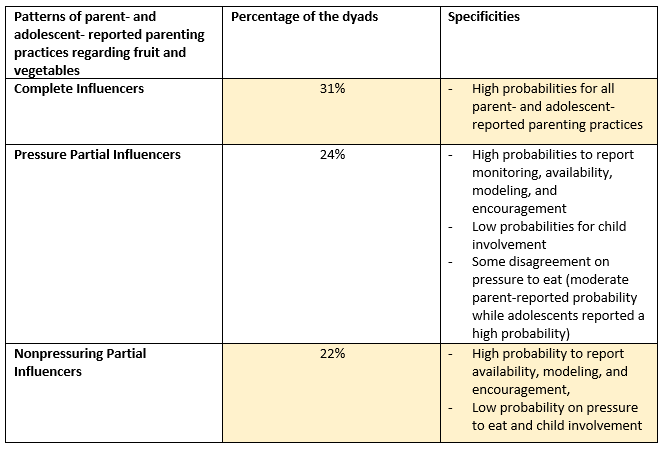

Five patterns emerged from the data representing parents and adolescents who reported complete use of the six parenting practices (complete influencers), use of some of the practices (Pressure Partial Influencers, Nonpressuring Partial Influencers, and Disagreeing Influencers), and use of few practices (Indifferent Influencers) (Table 2).

Combination of availability, modeling, and encouragement may be the most effective for promoting fruit and vegetable intake

Complete and Nonpressuring Influencers were the classes with the highest parent and adolescent parent and adolescent fruit and vegetables intakes. They were also those who showed high use of availability, modeling, and encouragement, suggesting that the combination of those three practices may be more effective for promoting fruit and vegetable intake than the other practices measured. However, further research is needed to confirm this finding.

The odds of belonging to one of the four classes, other than Complete Influencers (reference class), were between 19% and 63% lower for every one cup equivalent in parent fruit and vegetable intake. Though, for every one cup equivalent increase in adolescent intake, there is 55% lower odd to belong to Indifferent Influencers.

Positive associations were observed between fruit and vegetable parenting practices and fruit and vegetable legitimacy of parental authority

The study’s findings also suggest that the more parenting practices were perceived as used, the more likely parents and their adolescents are to agree that parents have legitimate authority to set rules about child’s fruit and vegetable intake.

Based on : Thomson JL, et al. Patterns of Food Parenting Practices Regarding Fruit and Vegetables among Parent-Adolescent Dyads. Child Obes. 2020;16(5):340-349.

- Distinct patterns of parenting practices exist and are associated with parent and adolescent demographic characteristics, dietary intake, and legitimacy parenting authority.

- The combination of availability, modeling, and encouragement practices may be more effective for promoting fruit and vegetable intake than the other practices measured.

- Considering that parents are not all the same in their use of parenting practices, a more personalized approach may be needed, when designing interventions to positively affect children’s dietary intake.