The impact of nutrition education and cash-value vouchers on consumption of fruits and vegetables

The Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants and Children (WIC), funded by the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA), provides nutritious food, nutrition education and breastfeeding support to low-income pregnant and postpartum women, and children up to age five. About half of all children in the United States receive services from WIC at some point between birth and age five1. Nationwide 9.1 million women and children receive WIC benefits,1 with nearly 1.5 million enrolled in WIC in California alone2. The WIC Program is different from other USDA nutrition programs in that only specific foods are included in the WIC food package and WIC participants can use WIC checks or Electronic Benefit Transfer (EBT) cards to purchase only those specified foods. The year 2009 marked an historic change to align the WIC food package with the 2005 Dietary Guidelines for Americans. Nationwide, fruits, vegetables and whole grains were included in the WIC food package for the first time, and milk purchases were restricted to lower fat for all women and children over two years of age3. Currently, there is great interest in identifying the impact of the new food package on WIC participant behavior, particularly with respect to fruit and vegetable intake.

The California WIC Nutrition Education and Food Package Impact (NEFPI) study

The NEFPI study took place from April 2009 – April 2010, spanning the October 2009 food package change. This was a naturalistic study based on cross-sectional comparisons of survey results. Identical survey methodology was used with distinct random samples of about 3,000 California WIC participants at three time points:

- Time 1 (March 2009): six months before the changes to the food package and prior to any education regarding the changes;

- Time 2 (September 2009): after education related to the new WIC foods but immediately before the change to the new food package;

- Time 3 (March 2010): six months after the change to the new food package.

The nutrition education session focusing on fruits and vegetables was conducted with all WIC participants in April and May of 2009. Titled “Get Healthy Now,” the session had two key messages: eat a rainbow of fruits and vegetables, and eat more “anytime” foods (with an emphasis on fruits and vegetables) and fewer “sometimes” foods. The curriculum was designed specifically for the California WIC population, which is largely Latino (>75%)2.

At all three time points, fruit and vegetable intake was assessed in two ways: frequency of respondent intake in the past week, and reported change in intake for the respondent and her family compared to six months earlier. Frequency of the past week’s intake was assessed separately for fruits and vegetables, with answer options ranging from 0, 1-2, 3-4 and 5-6 times per Week to 1, 2, 3 and 4+ times per day. Answer options for change in intake of respondent and family were: more, less, or about the same.

Increased consumption of fruits and vegetables after implementation

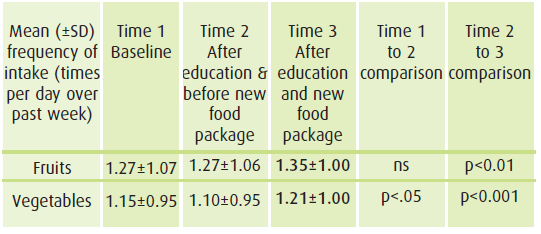

The mean frequency of fruit and vegetable intake by the respondents in the past week did not increase based on education alone, but increased significantly after implementation of the new food package.

The proportion of respondents who reported their family eating more fruit and more vegetables compared to six months earlier also increased significantly after implementation of the new food package (53 vs. 50.2% for fruits (p<0.05) and 44.1 vs. 39.3% for vegetables (p<0.001)). Respondents also reported eating significantly more fruits after education alone (50.2 vs. 42.8%, p<0.001).

Results of this study, published in part in the Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior4, suggest the changes to the WIC food package had positive impacts on WIC participant consumption of fruits and vegetables. Issuance of cash-value vouchers for fruits and vegetables appears to significantly increase participant consumption of both fruits and vegetables, with perhaps the greatest influence on vegetable consumption. The impact of nutrition education alone on participant consumption of fruits is also compelling.

More evidence is needed, but it could be that fruit consumption is more amenable to nutrition education, whereas monetary incentives are needed to increase vegetable intake. The good news is that WIC food package provisions of fruit and vegetables are making a difference on participant intakes.

References

- PHFE WIC Program, 2. Dr. Robert C. & Veronica Atkins Center for Weight and Health, UC Berkeley, 3. California WIC Program – USA

- Oliveira V, Frazao E. The WIC Program: Background, Trends, and Economic Issues, 2009 Edition. Economic Research Report No. 73, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service, April 2009.

- California WIC Association. WIC Facts & Figures. Available at: http://calwic.org/facts.aspx. Accessed January 2011.

- DiSogra C, Hudes M. California Fruit & Vegetable Intake Calibration Study. Award No. 99-86877, Cancer Research Program, California Department of Health Services, August 9, 2005.

- Ritchie LD, Whaley SE, Spector P, Gomez J, Crawford, PB. Favorable Impact of Nutrition Education on California WIC Participants. Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior, 42, S2-10.