Barriers and facilitators to improve fruit and vegetable intake among WIC-eligible pregnant latinas

Fruit and vegetable consumption during pregnancy

The potential maternal and infant health benefits of increasing prenatal fruit and vegetable (F&V) intake suggest it is a key intervention point for supporting optimal pregnancy and birth outcomes. Yet, improving F&V consumption during pregnancy requires modifying prenatal dietary behavior. Pregnancy is an ideal time, a true “teachable moment”, when women may be more committed to adopting healthier behaviors to minimize the health risks to themselves and their unborn baby1. Helping women to increase their prenatal F&V intake requires assisting them to bridge the gap between their intention to increase prenatal F&V intake (i.e. intention to change) and actually increasing F&V intake (i.e. the action itself) through proper planning.

The Health Action Process Approach (HAPA)

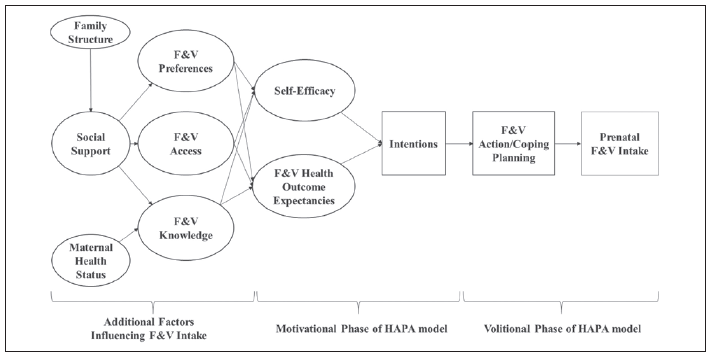

The Health Action Process Approach is a behavior change model that identifies key areas in the adoption and maintenance of health behaviors that can help a woman move from intentions to behaviors through action and coping planning2,3. This model emphasizes two distinct stages involved in the behavioral change process, a motivational phase and a volitional phase (Figure)2,3. In the motivational phase of the HAPA model, F&V health outcomes expectancies (i.e., the health outcomes women expect for themselves and their babies if they do not eat F&Vs during pregnancy) help a woman to weigh the pros and cons of consuming more F&Vs during pregnancy. Taking into account their outcome expectancies, women consider whether they have the ability (or perceived self-efficacy) to change their behavior (e.g., eating more F&Vs during pregnancy even with cravings for junk food). Both perceived self-efficacy and F&V health outcomes expectancies help a pregnant woman form an intention to increase prenatal F&V intake. In the volitional phase, the intention to change F&V intake becomes transformed into specific action plans which define when, where, and how to increase F&V intake. In this phase the coping plans to address potential barriers that might hinder more F&Vs intake during pregnancy are also developed.

Study objectives

We conducted forty-five in-depth interviews with low-income pregnant overweight/obese Latinas eligible for the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) to: 1) identify barriers and facilitators to prenatal F&V intake, and 2) inform a conceptual behavior change model based on the HAPA framework to improve their prenatal F&V intake4.

Barriers and facilitators to prenatal F&V intake

Social support was the primary driving force behind prenatal F&V intake among WIC-eligible Latinas. Family/friends were the principal source of emotional, psychological, instrumental (i.e. money or food), and informational F&V support. This support empowered women to initiate eating F&Vs or return to consuming F&Vs prenatally. Lack of familial support signified a lack of a cohesive family structure, making women feel isolated and alone, which discouraged them from cooking and eating healthy, negatively affecting their prenatal F&V intake.

Several barriers emerged influencing prenatal F&V intake. F&V access was limited due to lack of easily accessibly supermarkets within the city, limited availability of F&Vs at local convenience stores, and the high cost of F&Vs. Distinct F&V dislikes resulted from unpleasant tastes/smells, cravings for junk food, spoiled F&Vs, and cultural F&V preferences, subsequently discouraging prenatal F&V intake. Women experiencing pregnancy complications, such as gestational diabetes, decreased their prenatal F&V intake to improve their prenatal health status.

Higher F&V knowledge, increased self-efficacy, intentions to change, and having F&V action/coping planning strategies facilitated prenatal F&V intake. Women with higher F&V knowledge understood the health benefits of F&Vs for a mom and her unborn baby and/or knew how to cook F&Vs. Self-efficacy was higher for women who were already consuming/enjoying F&Vs and believed that they could improve the health outcomes for themselves and their unborn baby by consuming more F&Vs prenatally. Intending to change meant that there was strong internal and external motivation to increase prenatal F&V intake. Action and coping planning strategies (e.g. masking undesired F&Vs flavors) facilitated an increase in prenatal F&V intake.

F&V health outcome expectancies also played a role. Women associated poorer maternal and fetal health outcomes expectancies (e.g. suboptimal fetal growth) with less prenatal F&V intake, and better outcomes (e.g. preventing pregnancy complications) with higher prenatal F&V intake.

F&V behavioral change model utilizing HAPA

Self-efficacy, F&V health outcome expectancies, intentions to change, and F&V action/coping planning strategies were reflected in our results, showing that the HAPA model is relevant for a F&V behavior change model to increase prenatal F&V intake among WIC-eligible Latinas. Six additional factors were identified as essential to prenatal F&V intake: family structure, social support, F&V preferences, F&V access, F&V knowledge, and maternal health status. The HAPA model was expanded to include these distal factors, which each influenced self-efficacy and F&V health outcome expectancies, leading to intentions developing, F&V action/coping planning strategies being adopted, and subsequently affecting prenatal F&V intake.

Conclusion

The HAPA model proved to be very useful in identifying a behavior change model that includes additional key factors that need to be addressed to improve the likelihood that pregnant WIC Latinas can increase their prenatal F&V intake and improve related pregnancy health outcomes.

References

- Phelan S. Pregnancy: a “teachable moment” for weight control and obesity prevention. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2010; 202(2): 135 e1-8.

- Schwarzer R. Modeling health behavior change: How to predict and modify the adoption and maintenance of health behaviors. Applied Psychology 2008; 57(1): 1-29.

- Schwarzer R. How to overcome health compromising behaviors. European Psychologist 2008; 13(2): 141-51.

- Hromi-Fiedler A, Chapman D, Segura-Perez S, et al. Barriers and Facilitators to Improve Fruit and Vegetable Intake Among WIC-Eligible Pregnant Latinas: An Application of the Health Action Process Approach Framework. J Nutr Educ Behav 2016; 48(7): 468-77 e1.