Choice architecture to increase WIC fruit and vegetable purchases: Improving visibility and quality of fresh produce in urban corner stores

In 2009, the U.S. Department of Agriculture revised the Special Supplemental Program for Women, Infants and Children (WIC) food packages to provide cash-value vouchers for purchase of fruit and vegetables. In low-income, urban neighborhoods, many corner stores accept WIC vouchers and are where families shop for groceries. Typically, the most prominent items displayed in corner stores, near the entrance and the check-out counter, include unhealthy snacks, sugar-sweetened beverages, and baked goods. Fresh fruit and vegetables have limited shelf space, are located in the back of the stores, and are often of poor quality. “Choice architecture” interventions place healthy food and beverages in highly visible and convenient positions in order to increase sales and selection of these items. This study was a randomized, controlled trial of six corner stores in a low-income community to determine if a choice architecture intervention that increased the visibility and quality of fresh produce would result in increased redemption of the WIC fruit and vegetable vouchers.

Participation and randomization of urban corner stores

Corner stores were recruited in Chelsea, Massachusetts, a low-income urban community located near the city of Boston. Stores were eligible to participate if they accepted both WIC and Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) benefits and if they agreed to be randomized to the intervention or to the control group that did not receive the intervention. Stores were recruited in the spring of 2013, and three stores were assigned to the intervention during November 2013. The intervention period lasted from December 2013 through April 2014.

Study staff worked with intervention stores to determine which changes would be feasible and acceptable for each store. Depending on needs, the store was provided with basic supplies to set up produce displays (shelving, baskets, etc.) near the front of the store. Each store owner also met with a “produce consultant” who provided advice about how to stock and maintain a higher quality of fresh fruit and vegetables. Each store was responsible for choosing and ordering their own produce.

Choice architecture increased WIC fruit and vegetable voucher sales

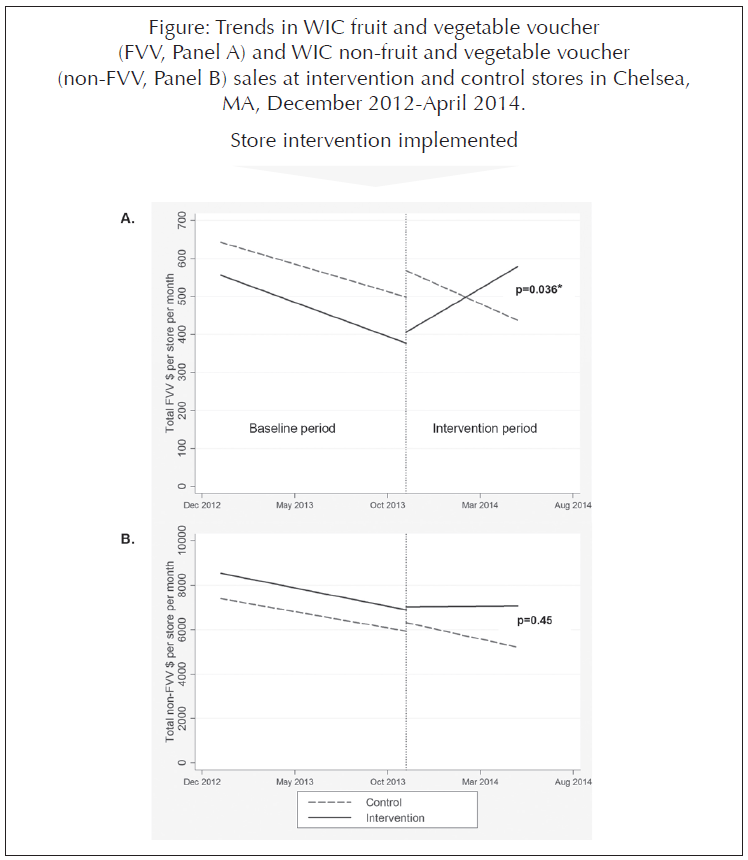

The primary outcome was sales with the WIC fruit and vegetable cash-value vouchers at the study stores. The Massachusetts state WIC office provided aggregate monthly sales data for each of the participating stores. Trends in fruit and vegetable voucher and non- fruit and vegetable voucher sales during the baseline and intervention periods are shown in the Figure. Before the intervention period (December 2012-October 2013), fruit and vegetable voucher and non- fruit and vegetable voucher (i.e., used for bread, milk, and other food staples) sales decreased similarly in both intervention and control stores by an average of $16/month. During the intervention period (December 2013-April 2014), fruit and vegetable voucher sales increased in the intervention stores by $40/month but decreased in the control stores by $23 per month (p=0.036), (Figure, Panel A). Non- fruit and vegetable voucher sales during the intervention period were not different between the intervention and control stores (p=0.45), (Figure, Panel B).

WIC and SNAP customers reported more fruit and vegetable purchases

Secondary outcomes were self-reported purchase of fruit and vegetables by customers who were interviewed when exiting the study stores during the baseline period and at the end of the intervention period. Overall, 23% (134/575) of exit interview participants reported they used WIC, and 37% (212/575) reported using SNAP. Among all exit interview participants, there was no significant difference between intervention and control store customers in the change in purchasing fresh fruit and vegetables or in planning to purchase fresh fruit and vegetables (before entering the store) between the baseline and intervention periods. However for customers using SNAP benefits, the change from baseline to the intervention period in customers reporting they purchased fresh fruit and vegetables was significantly higher for intervention store customers than for control store customers (6% vs. -15%, p=0.007), and the change in the proportion of those reporting that they planned to purchase fresh fruit and vegetables before entering the store was also higher (3% vs. -15%, p<0.001). There were similar but not statistically significant changes for customers using WIC for reporting purchasing (18% vs. -2%, p=0.11) and planning to purchase (15% vs. -6%, p=0.17) fresh fruit and vegetables.

Implications for improving fresh produce purchases in low-income communities

This study demonstrated that a simple choice architecture intervention to improve the visibility and quality of fresh produce resulted in increased purchase of fruit and vegetables by corner store customers participating in the WIC program, based on objective state-level data. The exit interviews indicated that intervention store customers using SNAP also increased purchase of fresh produce. In the future, the United States Department of Agriculture might consider policies for WIC and SNAP-certified stores that encourage displaying fruit and vegetables at the front of the stores and that provide education for stores about how to stock and maintain fresh produce. These policies could help improve healthy food choices and reduce disparities in obesity in lowincome families.

Based on: Thorndike AN, Bright OM, Dimond MA, Fishman R, Levy DE. Choice architecture to promote fruit and vegetable purchases by families participating in the

Special Supplemental Program for Women, Infants and Children (WIC): randomized corner store pilot study. Public Health Nutrition. 2016 Nov 28:1-9. [Epub ahead

of print] DOI:10.1017/S1368980016003074.