Consumption of 100% fruit juice, whole fruit, and vegetables among WIC-enrolled children compared to nonparticipants

There is controversy around the amount of 100% fruit juice allocated to children as part of the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) food package. While 100% fruit juice provides some essential vitamins and minerals, the bulk of the evidence suggests that consumption may be harmful to children’s health since juice provides nearly as much sugar as a can of soda, and lacks the health benefits of whole fruit1. While intake of certain fruit has been associated with positive health outcomes (e.g., reduced risk of diabetes), fruit juice consumption seems to do just the opposite2, and is linked to weight gain and dental caries among young children3. Further, there is some evidence that consuming fruit juice in early childhood increases children’s preferences for sweet taste and leads to greater consumption of other sugary beverages, like soda, later in life4.

Despite recently reducing the fruit juice allotment by nearly half, the WIC food package currently includes 128 ounces of 100% fruit juice, which provides 71% to 108% of the upper limit recommended by the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP). The current allowance for juice may be too high for several reasons. First, WIC is intended to be supplemental, and it is possible that families are already purchasing fruit juice through other means, such as with cash or Supplemental Nutrition Assistant Program (SNAP) benefits. Second, many children enrolled in WIC also participate in other nutrition assistance programs that serve juice (e.g., Head Start). Thus, children participating in WIC may have access to more fruit juice and may be more likely to exceed the AAP recommendations than nonparticipants. To test this hypothesis, we used national data to compare 100% fruit juice, whole fruit, and vegetable intake between WIC-enrolled children, incomeeligible nonparticipants, and higher income nonparticipants following the 2009 revisions to the WIC food package.

Nationally representative data source of WIC-enrolled children and nonparticipants

Data for this analysis comes from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys (NHANES), a nationally representative survey of the health and nutrition status of Americans. To obtain a sufficient analytical sample, we pooled together three NHANES surveys from 2009-2014. We included 1,576 children aged 2-4 years, of which 677 were WIC participants, 409 were income-eligible nonparticipants (household income ≤185% of the federal poverty line), and 490 were higher-income nonparticipants (household income >185% of the federal poverty line). A child was considered a WIC participant if their household reported receiving WIC benefits in the past 12-months. To calculate 100% fruit juice, whole fruit, and vegetable intake, a 24-hour recall was used, with primary caregivers reporting on behalf of their children.

We used linear regression to examine the association between WIC participation and daily 100% fruit juice, whole fruit and vegetable intake. We used logistic regression to assess the association between WIC participation and the odds of exceeding the AAP daily recommendations for 100% fruit juice. All analyses controlled for child sex, age, race/ethnicity, and weight status, as well as parental marital status, education, income-to-poverty ratio, and SNAP participation.

100% fruit juice, whole fruit and vegetable intake by WIC participation status

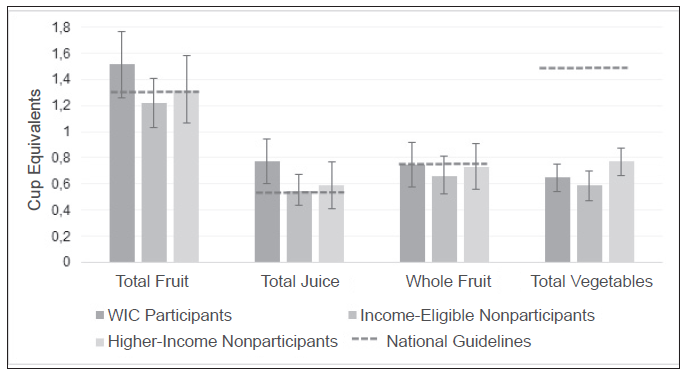

On average, WIC-enrolled children consumed 0.77 cup-equivalents per day of 100% fruit juice (equal to 6.2 ounces day), 0.75 cup-equivalents per day of whole fruit, and 0.65 cup-equivalents per day of whole vegetables.

Compared to income-eligible nonparticipants, WIC-enrolled children consumed significantly more 100% fruit juice, with WIC-enrolled children having a 1.51-fold greater odds of exceeding the maximum intake of 100% fruit juice recommended by the AAP (Figure 1). Compared to higherincome nonparticipants, WIC-enrolled children consumed significantly fewer vegetables

Figure 1: Adjusted Intakes of Total Fruit, Juice, Whole Fruit and Vegetables

Comparing WIC Participants with Nonparticipants

Reprinted from American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 55(1), Vercammen KA, Moran AJ, Zatz LY, Rimm EB, 100% Juice, Fruit, and Vegetable Intake Among Children in the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children and Nonparticipants, 11-18, Copyright (2018), with permission from Elsevier

Compared to income-eligible nonparticipants, WIC-enrolled children consumed significantly more 100% fruit juice, with WIC-enrolled children having a 1.51-fold greater odds of exceeding the maximum intake of 100% fruit juice recommended by the AAP (Figure 1). Compared to higherincome nonparticipants, WIC-enrolled children consumed significantly fewer vegetables.

Findings support reduction of 100% fruit juice in WIC food packages

The results of this study indicate that children participating in WIC are more likely to exceed the AAP guidelines for 100% fruit juice than incomeeligible nonparticipants. Additionally, all children in the study sample had a low intake of whole fruit and an insufficient intake of vegetables. These findings support reducing the 100% fruit juice allowance in the WIC food package and re-allocating funds towards the fruit and vegetable cash value voucher5,6.

Based on: Vercammen K, Moran A, Zatz L, Rimm E. (2018) A Comparison of 100% Fruit Juice, Whole Fruit and Vegetable Intake between Children Participating in WIC and

Nonparticipants. American Journal of Preventive Medicine.

References

- Heyman MB, Abrams SA. Fruit Juice in Infants, Children, and Adolescents: Current Recommendations. Pediatrics. 2017:e20170967.

- Muraki I, Imamura F, Manson JE, et al. Fruit consumption and risk of type 2 diabetes: results from three prospective longitudinal cohort studies. Bmj. 2013;347:f5001.

- Shefferly A, Scharf RJ, DeBoer MD. Longitudinal evaluation of 100% fruit juice consumption on BMI status in 2–5‐year‐old children. Pediatr Obes. 2016;11(3):221-227.

- Sonneville KR, Long MW, Rifas‐Shiman SL, Kleinman K, Gillman MW, Taveras EM. Juice and water intake in infancy and later beverage intake and adiposity: could juice be a gateway drink? Obesity. 2015;23(1):170-176.

- Ferris HA, Isganaitis E, Brown F. Time for an End to Juice in the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children. JAMA Pediatr. 2017.

- Nagata JM, Djafari JT, Chamberlain LJ. The option of replacing the special supplemental nutrition program for women, infants, and children fruit juice supplements with fresh fruits and vegetables. JAMA Pediatr. 2016;170(9):823-824.