How does the intake of fermentable carbohydrate alter barrier function ?

With a global prevalence of 11.2% in 2012 (Oka, 2020), irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is a common functional disorder characterized by abdominal pain, erratic bowel habits, and variable changes in stool consistency, yet the causes are insufficiently understood (Enck, 2016). While IBS treatment is proven difficult, dietary interventions can be a useful treatment for IBS, particularly the low-FODMAP approach that is gaining interest in recent years. Indeed, the fermentation of these unabsorbed carbohydrates by the gut microbiota can produce toxic glycating metabolites with potential harmful effects by generating advanced glycation end products (AGEs), which activates Receptor for AGEs (AGER) and support a pro-inflammatory state. Mast cells can also be activated by AGEs (Sick, 2010) through AGER activation, or by aldehydes (acetaldehyde) directly (Ferrier, 2006).

The present study (Kamphuis, 2022) conducted on mouse model investigates the implication of an increased intake of dietary fermentable carbohydrates in mucus barrier particularities, which could be involved in further epithelial barrier dysfunction. Mice were treated with lactose or fructo-oligosaccharides (FOS), with or without co-administration of pyridoxamine (see methodology below).

Lactose and fructo-oligosaccharides (FOS) dysregulate the colonic mucus barrier in mice

According to the study, an increased intake of lactose and fructo-oligosaccharides induces a dysregulation of the colonic mucus barrier, increasing mucus discharge in empty colon, while increasing variability and decreasing average thickness mucus layer covering the fecal pellet.

More specifically, mice treated with 5 mg/day of lactose had an 11.9% reduction in average fecal mucus layer thickness compared to those who did not receive lactose (control group). They also showed a 98% increase in the coefficient of variability (CoV) compared to the control group. Similar results were observed with diets containing 10% FOS. Indeed, mice treated with FOS had a 33% reduction of the average fecal mucus layer thickness compared to the control group, with a significantly increased CoV (+26% compared to the control group). Co-treatment with pyridoxamine normalized all the increases observed.

Also, an increase in mucus production was observed in both lactose-and FOS-treated mice, as demonstrated by the increased goblet cell discharge in empty distal colon. An increased mucus production was somewhat paradoxically accompanied by a reduced fecal mucus barrier formation and a higher variability in this mucus layer, which could explain the changes in fecal mucus layer thickness. Again, this effect was lost or moderated by co-treatment with pyridoxamine.

Hypothetical cascade on the effects of FODMAP ingestion

The authors observed that the negative effects listed previously and their prevention by co-treatment with pyridoxamine could be associated with changes in AGE levels in the intestinal tissue. Indeed, lactose and FOS treatment have increased the levels of carboxy-methyl lysine (CML), a main AGE residue, in the colonic epithelium (lactose +21,5% and FOS: +60% vs. control). Pyridoxamine co-treatment was able to prevent this increase, implicating glycation processes in the negative impact of fermentable carbohydrate ingestion.

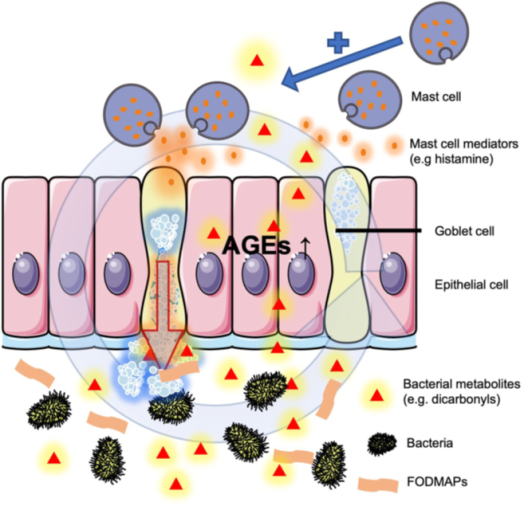

Therefore, together with the other effects observed on goblet cell activity, mast cell numbers, and mucus layer variability, a hypothetical cascade could be imagined (figure 1):

- The specific increased carbohydrate fermentation causes production of reactive glycation agents by the intestinal microbiota, leading to local production of AGEs in tissues exposed to these toxic metabolites.

- This, in turn, activates and upregulates AGER, activates mast cells and increases their number locally.

- At the same time, increased mast cell numbers and mediator production causes goblet cells to discharge more, even in the absence of contents, which causes the observed dysregulation.

- An increased intake of fermentable carbohydrates can cause colonic mucus barrier dysregulation in mice, by a process that involves glycating agents and increased mucosal mast cell counts.

- More specifically, an increased intake of lactose and fructo-oligosaccharides induces a dysregulation of the colonic mucus barrier, increasing mucus discharge in empty colon, while increasing variability and decreasing average thickness mucus layer covering the fecal pellet. AGE levels were also increased in colonic epithelium.

- Changes were correlated with increased mast cell counts.