The Effects of Blueberry Flavonoids on Mood in Young People

Depressive disorders: a public health issue

According to the WHO, depressive disorders are the second most common cause of death in young people because of the link between suicide and depression. Psychological therapies and a single licenced pharmacological treatment, Fluoxetine, are recommended as treatment for adolescent depression. However, they are only moderately effective, with up to 50% of young people not responding to treatment or experiencing relapse and further episodes of depression. An important area for development therefore is to prevent depression via public health interventions that can be delivered to a whole population of children and adolescents.

Fruit & vegetable consumption reduces the incidence of depression

There is emerging evidence linking diet and the onset of depression. Epidemiological data shows that lifetime consumption of fruit and vegetables predicts a lower incidence of depression in later life. In our recent review of the literature on diet and depression in young people, we found that although the quality of evidence was weak, there were consistent links between nutrition and depression in both cross-sectional and longitudinal studies. This may be attributed to the presences of high amounts of nutrients called flavonoids. Flavonoids are a class of polyphenols (micronutrients) found naturally in fruit, vegetables, tea, coffee and cocoa. However, there is an absence of studies exploring the effects of flavonoid-rich interventions on mood.

Wild blueberry drink increases the positive emotional state

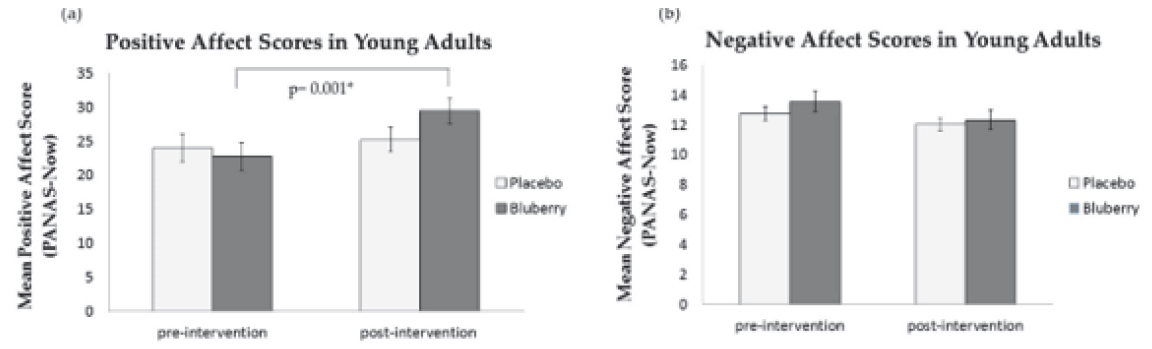

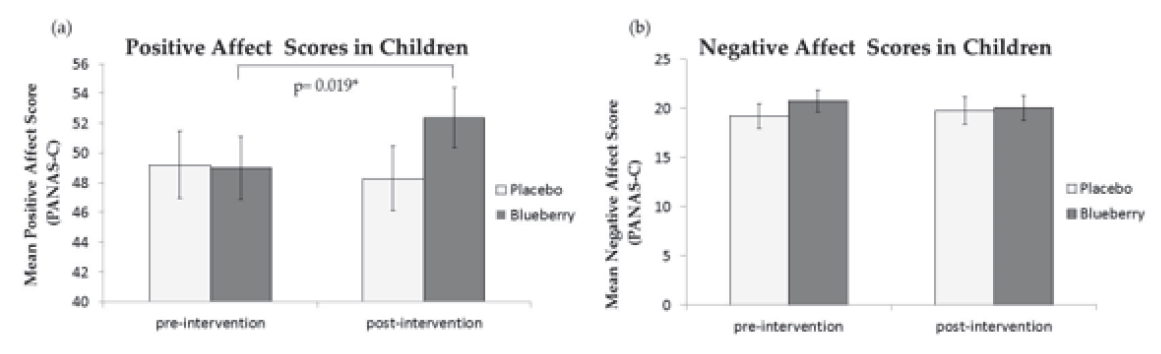

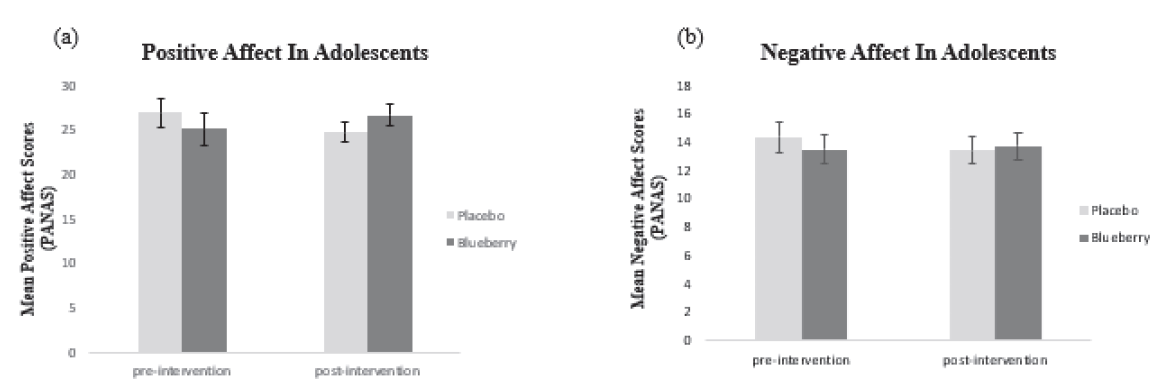

Given the well-documented links between fruit and vegetable consumption and depression, we tested the acute effects of flavonoidrich wild blueberries (WBB) in a double blind randomized trial. We carried out 3 independent studies, with healthy children (7-10 years) N=50, adolescents (12-17 years) N=33 and young adults (18-21 years) N=21. All participants were randomised to either a WBB drink (equivalent to 240g of fresh WBB) or a placebo drink (matched for sugars and vitamins). They were asked to complete a questionnaire measuring their negative (NA) and positive (PA) emotional states (the Positive and Negative affect schedule; PANAS) before and 2 hours after consumption. This period represents the time of peak absorption and metabolism of blueberry flavonoids. We analysed the data from these studies using repeated measures ANOVA, mixed ANOVA and General linear modeling depending on the study design. Significant main effects and interactions were explored with Bonferroni corrected post-hoc t-tests. The effect of flavonoids on mood was consistent across all three of the studies, at different times of day (morning, afternoon and evening), and in a between- and a within-subject design. Young adults: There was a significant increase in positive affect after consuming the blueberry drink. There was no change in positive affect after consuming the placebo drink (Figure 1). Children: There was no significant change in positive affect after consuming the placebo drink, but a significant increase in positive affect after consuming the blueberry drink. There was no significant difference in NA between Placebo and WBB at the post consumption (Figure 2). Adolescents: There were no significant changes to positive affect or negative affect as a result of the drink. However, there was an increase in mean positive affect scores two hours post consumption, though this was not significant. No such effects of blueberry on negative affect were observed (Figure 3).

Figure 1. Mean PANAS-NOW Mood scores in adults aged 18-21 years: (a) Mean PA scores pre-and post-consumption of placebo and

intervention drinks (b) Mean NA scores pre-and post-consumption of placebo and intervention drinks.

Figure 2. Mean PANAS-C Mood scores in children aged 7-10 years: (a) Mean PA scores pre-and post-consumption of placebo and

intervention drinks (b) Mean NA scores pre-and post-consumption of placebo and intervention drinks.

* Significant at <0.05. Attained from post hoc paired t-test.

Figure 3. Mean PANAS-NOW Mood scores in adolescents aged 12-17 years: (a) Mean PA scores pre-and post-consumption of placebo

and intervention drinks (b) Mean NA scores pre-and post-consumption of placebo and intervention drinks.

Flavonoid may prevent dysphoria, a strong predictor of the emergence of major depressive disorder

Sustained periods of low mood or dysphoria (low positive affect) are a strong predictor of the emergence of major depressive disorder. Therefore, if acute flavonoid consumption improves positive affect, we hypothesis that sustained consumption of flavonoids may help prevent dysphoria, and thus the onset of major depression. Given that depression tends to emerge for the first time during adolescence and early adulthood, and typically leads to repeated episodes later in life, an intervention that increases flavonoid consumption during this critical period of development could decrease incidence of adolescent and lifelong depression.

Perspective: dietary intervention to promote positive mood

These studies demonstrated that consuming blueberry flavonoid improved positive affect and had no effect on negative affect in healthy children, and young adults. There seems to be similar effects of blueberry flavonoids on adolescent mood, however not significant. Dietary interventions, particularly F&V, could play a key role in promoting positive mood and are a possible way to prevent dysphoria and depression. Given the potential implications of these findings for preventing depression, it is important to replicate the study and assess the potential to translate these findings to practical, cost-effective and acceptable interventions.

Acknowledgments: We are grateful to the Wild Blueberry Association of North America who provided the freeze-dried wild blueberry powder used for this study.

Based on: Khalid S, Barfoot KL, May G, Lamport DJ, Reynolds SA, Williams CM. Effects of Acute Blueberry Flavonoids on Mood in Children and Young Adults. Nutrients.

2017;9(2):158. doi:10.3390/nu9020158.